News

Published on 31 Jan 2018

James Willoughby

Heliguy Interviews Raptor Aerial Imaging

Heliguy speak to Raptor Aerial Imaging on the application of drones in search and rescue missions. The used a DJI Matrice 200 series M210, Zenmuse XT and Z30. ... Read More

Heliguy Interviews Raptor Aerial Imaging Heliguy recently lent their valued customer, Tom Nash from Raptor Aerial Imaging, a DJI Matrice 210, Zenmuse XT thermal sensor and Zenmuse Z30 zoom camera.

Tom used the equipment to test out its real-world application as part of a several simulated mountain search and rescue scenarios and provided Heliguy with his feedback. Tom presented Heliguy with his findings and sat down for an interview to discuss his opinions on using drones to assist with search and rescue missions. Keep reading to find out whether drones, thermal cameras and zoom cameras can be beneficial as a practical tool in search and rescue.

About Raptor Aerial Imaging

Raptor Aerial Imaging is the company of Tom Nash, a former RAF Tornado GR4 navigator with close to 2000 hours flying. Tom has experience with operating multiple systems and, thermal and infrared sensors. He has served in both Iraq and Afghanistan as part of the RAF. As a qualified commercial drone pilot, Tom has logged over 200 flights and has experience in flying a number of aircraft, including the DJI Inspire Pro with a Zenmuse X5 Micro Four Thirds camera.

He has used drones for inspection and mapping, precision agriculture, photography and more. In December 2017, Heliguy lent Tom a DJI Matrice 210, a Zenmuse Z30 and Zenmuse XT to test how drones could potentially support a search and rescue team. As well as the above equipment, Tom also used his own DJI Phantom 3 and DJI Mavic Pro to cover drones from a consumer to enterprise level. 19 daytime flights were carried out, totalling 4 hours and 15 minutes. Each flight was used to evaluate the functionality of the aircraft, sensor, software, system integration and portability, as a support to theoretical search and rescue missions. Keep reading to find out what Tom thought about the equipment and the application of drones to support mountain rescue missions.

Raptor Aerial Imaging Findings

Following the thorough testing of the equipment in imitation search and rescue missions and generic test flights, Tom from Raptor Aerial Imaging has put together his key findings on the use of drones with thermal and zoom cameras, as well as the supporting accessories. Flights were conducted in various terrains and weather conditions expected on search and rescue missions.

DJI Matrice 210

Having used the M210 and its supporting equipment, I found the aircraft to be a very useful piece of equipment for search and rescue applications.

The following areas were particularly noteworthy during operation:

Single pilot operation was possible with the M210 and payloads when flying in an undemanding open and flat location. When flying as a single pilot, advanced flight skills, as well as sensor and image operation, are required to ensure safe and event-free.

It would be recommended a search and rescue team had multiple capable pilots and sensor operators. For the team, working in a pair for aircraft and gimbal control would be the most effective arrangement, with a potential third person for data management.

The DJI CrystalSky monitor was superb for control of the aircraft in all light conditions. It had an impressive battery life and worked seamlessly with the Cendence Remote Controller.

The CrystalSky provided strong results of the thermal imaging, however, viewing on an additional larger monitor in higher resolution straight from the SD card proved to be more useful. The new DJI FlightHub will likely aid this process as real-time external viewing would be possible however, this will be dependent on a data signal which in the mountains of Scotland is not all that common.

Issues may be encountered with flights in areas of mixed terrains varying in height. The main issue is caused by the aircraft calculating its height based on the takeoff point resulting in inaccurate data. Errors can be mitigated by takeoff from the highest location, but this will likely not be possible in a large number of search and recuse mission.

The use of the BETA DJI Pilot is not as advanced as appropriate for the M210 and supporting cameras and sensors. Capabilities that are available as part of other DJI software isn’t available which impacts on the usability for the pilot, significantly increases pilot workload and the likelihood of human factors related incident.

Although the kit is compact, it still proves difficult to transport if using two payloads and the maximum amount of kit. The cameras, second remote controller and second CrystalSky do not fit in the DJI case.

Using a vehicle when available is a must, potentially alongside CAA exemption which allows Emergency Services a more flexible approach to operation. Although using a vehicle may be an option, dislocated command and control with decisions being made by non-qualified drone pilots away from the immediate scene, weather conditions etc are fraught with potential danger.

Details of the exemption mentioned above can be found in the ORS4 No.1233: Small Unmanned Aircraft - Emergency Services Operations.

Payloads

The use of a dual payload combination with a thermal and zoom camera setup was ideal. The combination of the two cameras allowed rapid decision making and maximum flight. The following areas stood out regarding the payloads:

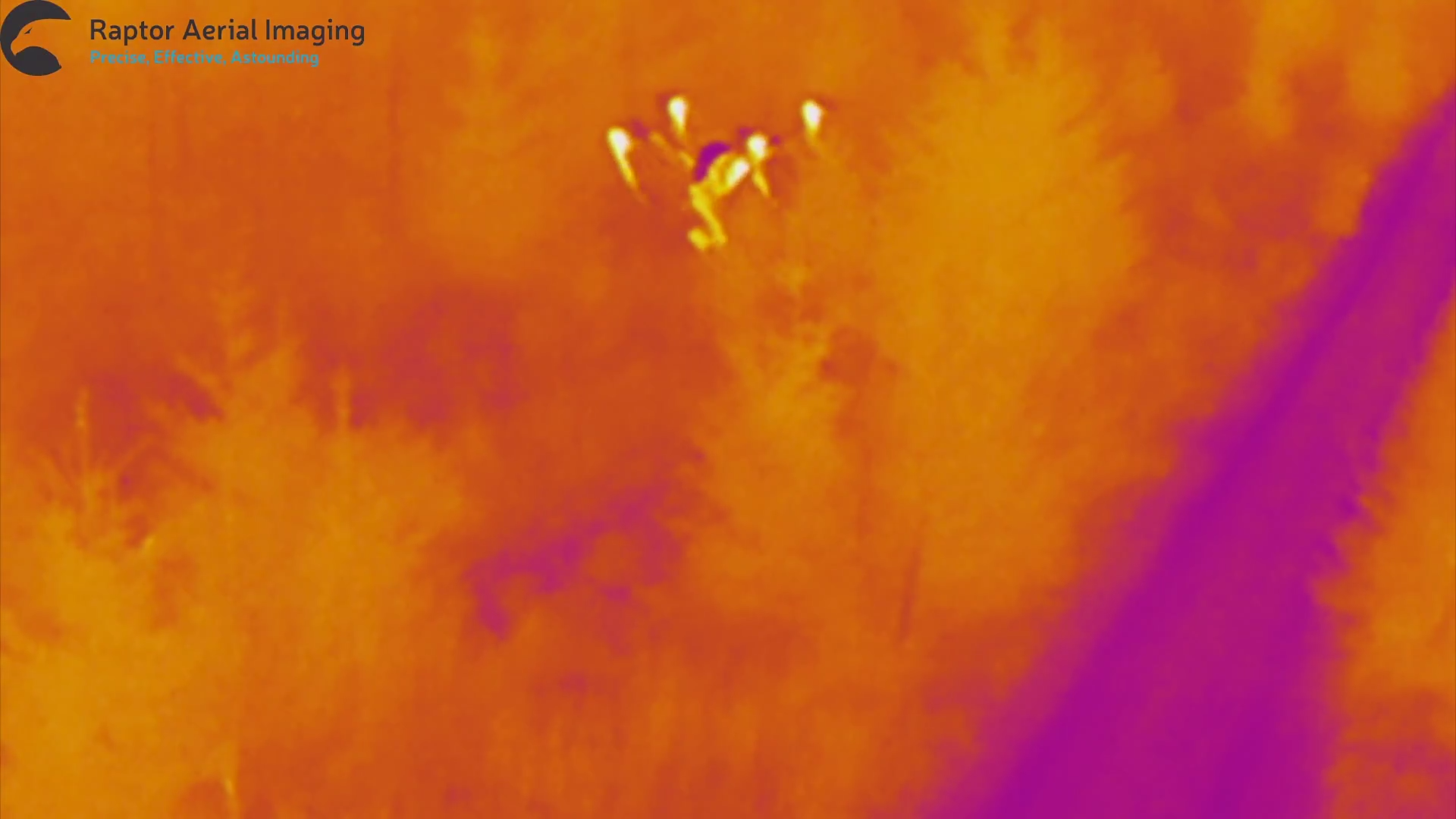

The use of the Zenmuse XT was best suited to locating heat signals from a person in open terrain at a range of up to 500m. Heat returns could, however, be blocked by an object including foliage which is to be expected with small, uncooled thermal cameras.

When testing the Zenmuse XT on an open hillside, five test individuals were located in under 30 minutes when using the thermal camera. This is significantly faster than the use of an on-foot team which could take several hours.

People who are lost when out hiking will often take a heat-blanket or survival bag to keep warm in an emergency When locating a person using a heat-blanket in a dummy scenario, the heat signal was halved, reducing the chance of finding the subject.

The Zenmuse Z30’s performance was outstanding. A human shape could be detected at 1500m meaning flight time could be increased as the search area did not necessarily need to be overflown. Any thermal signal detected could be investigated with the Z30 in a matter of seconds. Once a person was located, a visual triage of any injuries such as consciousness could be completed. The rescue plan can then be tailormade for the specific scenario.

Weather

In the UK, the weather can have a huge effect on the use and deployment of drones. The weather conditions in mountainous areas can be even more pronounced and localised conditions may be far from that forecast. Due to the above, the following areas should be considered:

Three flights were cancelled when winds exceeded 12m/s, the maximum speed DJI advise the M210 can be flown in. When flown in winds close to 12m/s the Matrice 210 performed well however, gimbal errors did occur resulting in footage that couldn’t be used. In some cases, the camera motors shut down entirely.

The M210 performed well in flight in sub-zero temperatures with high wind-chill. Pilots must be prepared for these conditions as keeping warm and maintaining dexterity for aircraft control was difficult.

The IP43 of the M210 is a must for search and rescue application, however, and IP rating on the sensor is also required.

Additional Points

When testing the use of the Phantom 3 and Mavic Pro to search larger areas, it’s clear the kit is unsuitable due to the range, lack of zoom, small sensor, overall camera etc. Despite this, there was an unexpected benefit to the use of smaller drones.

When deploying a manned search and rescue mission, drones can be used to provide an accurate comparison of terrain against an Ordnance Survey (OS) map. A quick flight can be completed with photographs taken, then displayed for the search manager. The photographs, used with the OS map allows the most precise search plan to be put into place. Knowing these details could improve the efficiency of the search and rescue team and be the difference between finding a casualty and not.

Interview

Following Tom reporting back his findings on the application of the Matrice 210, had the opportunity to ask him a few questions about his experience and opinion of drones as a solution for search and rescue.

What are the key benefits of using drones to support search a search and rescue team?

This is not as clear-cut as one might think. As proven during the trial flights, the find success rate can be very high. Five people in unknown locations, found in under 30 minutes is outstanding. However, the conditions need to be suitable. In this case, a wide-open hillside with little vertical foliage and a large temperature differential between the ‘casualty’ and environment as well as low wind.

Across the drone industry, I see people seeing drones as the ‘be all and end all’ which could not be further from the truth. They are simply another tool in the toolbox for the specialist user. Drones will not replace the human foot search, search dogs or helicopter support, however, in the correct scenario, they certainly augmented the teams’ ability to search immensely.

As a mountain rescue request comes in, it is assessed and then a call made on the capabilities required for that particular search; if the scenario requires a drone, it will be called upon. For this to be effective a clear understanding of capability must be held by the decision makers.

For me, the biggest surprise was how valuable a small aircraft can be to understanding a search area. Traditional maps, Google Earth etc. are always going to be out of date to some extent. The ability to put an aircraft up to ideally 400ft (although the wind did prevent this) and either provide a live feed or images of the terrain to the search manager, allows a more informed decision on search structure, equipment and manpower requirements to be made ahead of boots stepping onto the hill. This can be done now with cheaper aircraft provided the permission is in place from the operational risk holders.

How do you think the use of drones compares to traditional methods used for search and rescue?

As already alluded to, the use of drones needs to complement traditional methods of search and rescue. No matter how good the aircraft and sensors, it cannot operate in wild conditions or search obscured terrain such as woodland. A person and dogs can pretty much take on anything. Where a drone comes into its own is to help break down a search area into manageable areas. For example, the drone searches the wide-open hillside while the human foot search is concentrated in the neighbouring dense forest.

The other major issue I foresee for search and rescue teams is that they are predominantly made up of volunteers who have day jobs, family etc. Aviation operations and the safety thereof, are inherently intensive of time. When I look at the number of hours I have spent training, maintaining logbooks to the standard my NQE expect, keeping my operations manual up to date, conducting general handling to keep my skill sets up (especially in degraded modes) it is a lot.

The introduction of drones into any search and rescue operation will require significant detail, the nature of the operations will demand more safety procedures to be put in place and it is whether the organisation has the capacity to deal with that. It's different for a police force where it is part of their salaried job, so I see the support of organisations that specialise in the provision of aviation safety management systems and automated software solutions vital to charity rescue organisations. Whether a charity can afford their services is another topic.

Other than the use of smaller drones for comparison against OS maps, were there any other areas that surprised you about drone use during the test?

I was very surprised by how quickly poor software increases workload to a level where all I could do was concentrate on safe flight. Used to DJI GO, using the beta version of Pilot was a major step back. Since I have conducted the trial flying DJI GS Pro has been made available for dual camera operations which will hopefully be a big improvement. Flying a search pattern manually was incredibly taxing, especially in the weather I was often flying in and when one bit of forest looks identical to another. Automation of the search has to be at the forefront of research and development.

Understanding how it works is critical; as long as aircraft height is based upon the height above take-off and not AMSL based on some form of digital terrain elevation database, ill-planned or rushed missions could easily see aircraft flown into terrain. This is especially a factor in places such as Scotland, Wales and the Lake District.

What areas you think need to be developed for the successful integration of drone for search and rescue?

There are three key areas for me:

Weather robustness of the sensors as well as the aircraft. While the M210 was fantastic, when the sensors could not cope with more than 10m/s wind it is an expensive asset that will stay grounded a lot in Scotland!

Automation of the search both in terms of aircraft flying and also casualty detection. The addition of digital terrain elevation data into the aircraft so it knows height AMSL and can fly at a set height above the surface will not only make flying safer it will also mean the search will be more effective as consistency will be guaranteed for the sensor FOV, pixels per frame, swathe being imaged etc.

Education and training of all involved. The pilot needs to be confident in handling a drone in any condition whilst also providing the sensor outputs required by the search managers and decision makers. On top of this, they also need not be a liability to the rescue team themselves, be able to handle themselves in a rescue scenario and be able to conduct all the associated admin that comes with being a drone operator. This is not for the faint-hearted and I believe there should be a structured selection and training process for any pilot and sensor operator wanting to conduct SAR activity. The decision makers need to understand the realistic capabilities drones bring so they don’t expect results that can’t be delivered. The public need to be educated that drones are not all bad news and that, in these scenarios, they are being used to try and save lives.

How do you think the UK regulations impact drone use for search and rescue?

I think that the regulation is not tight enough at the moment and I look forward to seeing what comes from the Government’s new legislation. My fear is there will be good legislation in place but little enforcement, so people will continue to fly recklessly, endanger other airspace users and get away with it. With tighter, enforced regulation and the right training I actually see a positive impact for drone use in search and rescue as emergency services will become happier to employ the capability using pilots that have proven they operate to the level expected of a military or commercial airline pilot. The public will slowly see that drones are being used for good.

What advice would you give to a drone pilot interested in search and rescue?

Don’t think search and rescue is another string you can just add to your PfCO bow. The nature of search and rescue operations is demanding, high pressure, high expectation and generally in horrible weather conditions. As such, invest in further training, fly in degraded modes as much as you can, know how every mode works etc. The last thing you need in the dark and high winds is to hit RTH and find that RTH in that sub-mode means land in position!

Is there anything you recommend to people who might end up in a search and rescue situation?

If you are on the receiving end and needing to be found, do as much as you can to make yourself different from your surroundings; the trend seems to be for lots of dark colours in hiking equipment recently yet bright blue/orange/yellow tends not to appear naturally too often and helps you stand out. That way a camera on a drone might not make you out as a person but you become something different that then becomes worthy of further investigation. Have a charged phone, turn off the Wi-Fi and Bluetooth and put it into battery saving mode. Register your phone with http://www.emergencysms.org.uk so that you can send a text if the reception is not at a level to make a call. Finally, if you ever need mountain rescue, remember dial 999 and then ask for the police then mountain rescue.

Summary

Following Tom’s application of drones in simulation search and rescue mission, there are definite potential benefits of their use as a supplementary tool to a search and rescue team. Overall, the DJI Matrice 210 system was a strong performer, along with the Zenmuse XT and Z30.

Work is required with some of the equipment, however, DJI are constantly developing their enterprise kit and successfully moving forward with advancements. Recent releases of the FlightHub technology and developments of the GS Pro app show, along with the consumer sector, DJI are committed to their enterprise division. UAV technology is still in its nascent stages and has unlimited possibilities, especially within emergency services.

Find out more information on the use of drones as an enterprise solution here.

To discuss any information from the above post or any DJI drones or products, please give one of our team a call on 0191 296 1024 or email us at info@heliguy.com.

Keep checking back to Heliguy’s Insider Blog for more announcements, insights into drones and, of course, the latest news from the drone industry.